Grand Rounds

Human Herpesvirus-6 Encephalitis After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Heather L. Kasberg-Koniarczyk, MSN, NP-C, AOCNP®

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Author's disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found at the end of this article.

Heather L. Kasberg-Koniarczyk, MSN, NP-C, AOCNP®,

9500 Euclid Avenue, R32, Cleveland, OH 44195.

E-mail: heather.kasberg@gmail.com

J Adv Pract Oncol 2014;5:373–378 |

DOI: 10.6004/jadpro.2014.5.5.8 |

© 2014 Harborside Press®

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

CASE STUDY

Mrs. L. was in good health until she was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) at the age of 63. She had presented to her primary care provider with a productive cough and was found to have pancytopenia, with 16% myeloid blasts on a peripheral blood draw. She was admitted to a major metropolitan hospital for treatment of suspected AML. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, resulting in 44% myeloid blasts with complex cytogenetic studies [46,XX,der(16)t(1;16)(q21;q24)[2]/46,idem,t(4;16)(p12;q24)] and background ringed sideroblasts and dyserythropoiesis, implying underlying myelodysplasia in addition to AML. Molecular testing for FLT3, NPM1, and CEBPA was not performed, given the picture of antecedent myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). The French-American-British classification system traditionally used for AML cases is no longer applicable for MDS in light of the system revisions in 2008.

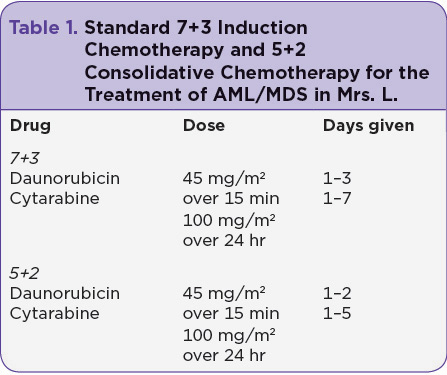

Mrs. L. began standard 7+3 induction chemotherapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine (Table 1). Her bone marrow biopsy on day 14 was negative for residual AML, and her course was complicated only by tenosynovitis of the left foot, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and culture-negative neutropenic fevers. Her posttreatment bone marrow biopsy was negative for AML but showed some residual dysplastic changes consistent with MDS; therefore, she received 5+2 consolidation chemotherapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine (Table 1). Following this regimen, Mrs. L. was rehospitalized for neutropenic fever. She developed sepsis from Streptococcus oralis, requiring intensive care for hypotension but no intubation. She completed a course of IV cefepime, recovered, and was discharged home.

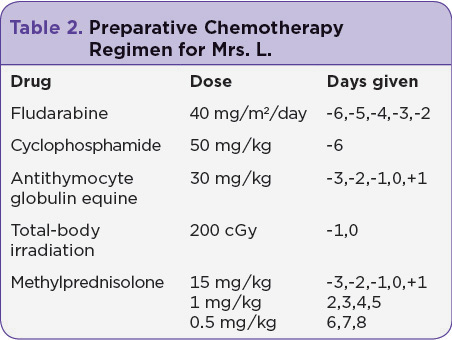

Due to the continued dysplasia in her bone marrow and the high risk for recurrence of AML, even after consolidative chemotherapy, Mrs. L. was referred for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), with the intent of a cure. Due to her age, she was found to be an acceptable candidate for a reduced-intensity chemotherapy preparative regimen using fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, antithymocyte globulin equine (ATG), high-dose methylprednisolone, and total-body irradiation (Table 2). The only source of donor stem cells that matched her human leukocyte antigen (HLA) was a multiple cord blood stem cell infusion consisting of two unrelated cord blood donations; cord A and cord B were infused without incident. Medications used to prevent graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) were tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil.

Mrs. L. became appropriately pancytopenic on day 5 after initiation of the HSCT preparatory regimen and was supported with blood and platelet transfusions. She developed oral mucositis on day 6 after the cellular infusion, as many HSCT patients do. She was treated with IV opioids and managed supportively with IV fluids and medications.

On day 3 posttransplant, Mrs. L.’s caregiver mentioned that she seemed confused. Upon examination, she was alert and oriented to person and place but not time. Her affect seemed unusual, and she responded to questions abnormally. At this time, she was neutropenic and severely immunosuppressed. Given the concern for sepsis, blood and urine cultures were drawn and a chest x-ray taken, but the results of all tests were negative.

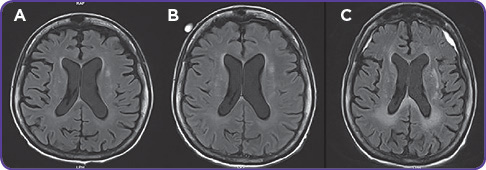

The following day—day 4 posttransplant—tacrolimus was discontinued due to concern for possible posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). She underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (see Figure, part A), which revealed no abnormalities. On day 7 posttransplant, a lumbar puncture (LP) was performed, with all blood cell counts, chemistries, and infectious cultures negative.

Mrs. L. began having neutropenic fevers along with progressive confusion the following day. She was oriented to person only. Neurology and infectious disease services were consulted. Blood and urine cultures were repeated, showing a vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) urinary tract infection (UTI). She was given daptomycin for 7 days, which resulted in clearance of the UTI but no improvement in her mental status. A second MRI of the brain was done on day 11 (see Figure, part B), which appeared to be normal.

Neurology recommended an electroencephalogram (EEG), which showed subclinical seizures. Mrs. L. was started on the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam, again with no improvement in her mental status. Additionally, she engrafted white blood cells, neutrophils, and other blood counts on days 25 through 28 posttransplant; a bone marrow engraftment study showed her blood was 100% cord A, signifying a successful engraftment, which can sometimes be difficult in cord blood transplant.

Mrs. L. eventually became nonverbal. A second LP was requested by neurology, infectious disease, and the transplant group, but her husband was hesitant for fear of causing her repeated discomfort. He eventually agreed, because she became progressively unresponsive. The LP was completed on day 27 posttransplant. Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) was identified, with 5,300 viral copies/mL in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and 41,000 viral copies/mL in the serum.

Mrs. L. was started on foscarnet therapy immediately. A repeat HHV-6 viral load was checked on day 14 following the initiation of foscarnet treatment. The CSF revealed no HHV-6, and there was a large reduction in the serum viral load, but there was no improvement in Mrs. L.’s neurologic status.

A third MRI of the brain was done on day 41 posttransplant, which showed new white matter changes consistent with leukoencephalopathy and bilateral frontal and parietal subdural hematomas with a mild mass effect (see Figure, part C); however, Mrs. L. was deemed a nonsurgical candidate by the neurosurgery service.

Neurosurgery, neurology, and infectious disease specialists agreed that inflammation from HHV-6 was likely the cause of her hematomas and that her prognosis seemed irreversible. After long discussions, her family chose palliative treatment alone. Mrs. L. passed away on day 48 posttransplant. Her death was likely caused by HHV-6 encephalitis with multiple subdural hematomas.

For access to the full length article, please

sign in.